Github Link

If you have completed the Part 1 of this series, which gave an introduction to the overall bytecode structure for the virtual machine, then this is a continuation of that same post. In this post I will explain the overall design of the VM before we proceed any further.

VM Architecture:

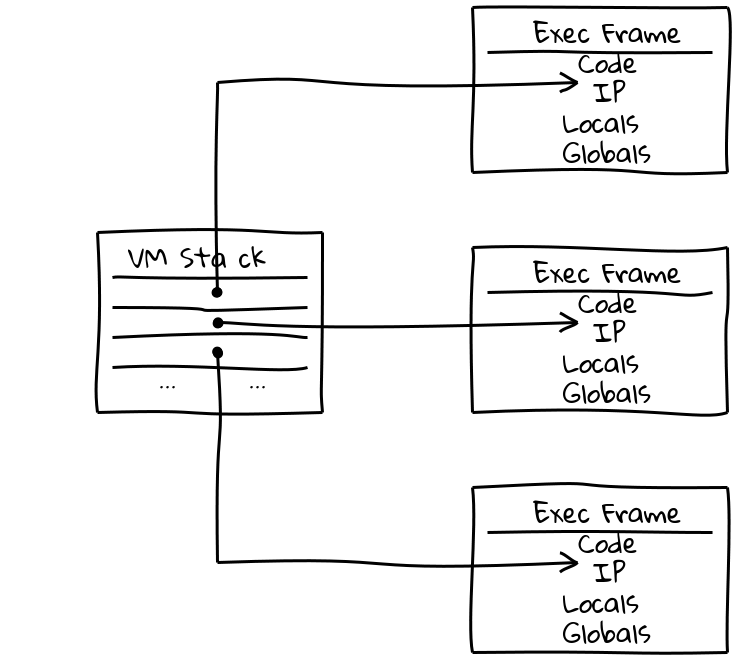

The diagram above shows the two main components present in the VM. An execution frame (exec frame) and the VM itself which maintains a stack of exec frames.

Execution Frame:

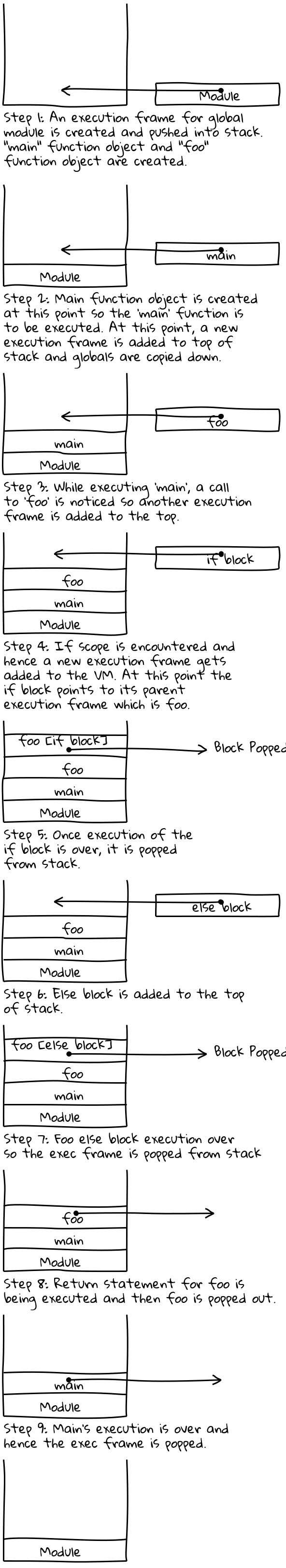

The execution frame can be thought of as a secluded object which can execute a piece of code. It maintains its own code object (which it receives from the python bytecode), an IP (also known as instruction pointer), the locals in the current scope and globals. An instruction pointer keeps track of which instruction is currently being executed. So the big question is why do we need an exec frame. The main purpose of an exec frame is to manage scope.

Scopes occur with different kinds of constructs in a language. For example, a module is the outermost scope so all variables, functions etc defined in module scope appear as globals. Functions, then provide the next level of scoping abilities. Locals can be defined within functions which need to be maintained. The next level of scoping comes from control flow (also known as blocks generated from if-else-endif, while loops, for loops etc).

So to manage these different kinds of scopes it is important to manage execution frames. I will give an example below.

def foo(a, b):

if a > b:

a = a + b

else:

a = a - b

return a

def main():

foo(3, 4)

main()

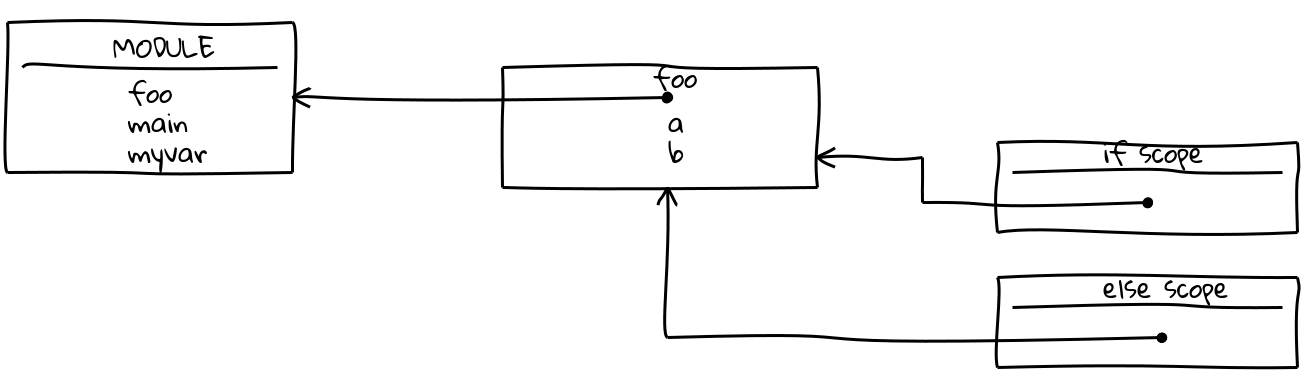

If you look at the function above it demonstrates a bunch of scopes. For example, the first one is the function foo and main. These 2 functions need to be present in the global scope of the module so that other functions can call it. This is how main is able to call foo by looking into the global scope of the module.

foo in turn has to maintain locals of a, b and then there is the if and else scope. The if and else scope have to be different execution frames since they could define their own variables in that scope. However, each execution frame has a reference to its parent execution frame.

Having this parent-child relationship enables an execution frame to go up the chain to figure out which local is being referenced. There are some more complex cases which I haven’t handled in my code yet. For example, the below code won’t work in the vm right now.

def foo(a, b):

if a > b:

d = a + b

else:

d = a - b

return d

def main():

foo(3, 4)

main()

In this, I changed the assignment to a new variable ‘d’ which is to be returned. So in this case we have to have this variable in the foo scope rather than in the if else scope. However, there could be variables which are present only in the if-scope or else-scope which are not used outside and have to be present in their respective scopes.

Program Execution

The diagram below shows the order in which the program given above executes.

Functions

def foo(a):

b = a * 5

print("Value of b: %s" % b)

return b

def main():

d = 5

e = 6

m = d + e

return foo(m)

main()

This example shows how function objects are created and how they are called. The bytecode for this is shown below.

1 0 LOAD_CONST 0 (<code object foo at 0x7fe7dc4e3f60, file "tests/call_func.py", line 1>)

3 LOAD_CONST 1 ('foo')

6 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

9 STORE_NAME 0 (foo)

6 12 LOAD_CONST 2 (<code object main at 0x7fe7dc4935d0, file "tests/call_func.py", line 6>)

15 LOAD_CONST 3 ('main')

18 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

21 STORE_NAME 1 (main)

12 24 LOAD_NAME 1 (main)

27 CALL_FUNCTION 0 (0 positional, 0 keyword pair)

30 POP_TOP

31 LOAD_CONST 4 (None)

34 RETURN_VALUE

The first line shows the code object for the foo function when it is created. On line 3 you will notice a MAKE_FUNCTION bytecode. This instructs the vm to create a new function object with the code loaded on the stack and then the name of the function is to be “foo” from line 2. The STORE_NAME then takes the function object created and stores it in the global dictionary and associates it with the key “foo”.

class Function(Base):

def __init__(self, name, defaults, code=None):

Base.__init__(self)

self.__name = name

self.__defaults = defaults

Base.set_code(self, code)

The above is the declaration of the function object which is used whenever a MAKE_FUNCTION is encountered.

Similarly, the same thing happens for the next 4 lines when “main” function is defined.

The last 5 lines are interesting since they start the execution of the VM. The VM loads the name “main” from the global dictionary and then calls the main function with no arguments. Generally if arguments are present they will be present at this call point. Default arguments are handled when the MAKE_FUNCTION is specified. Going into that will be too much details for this blog, however, running the VM and tracing through it will show how arguments are handled.

During the Call function, a new execution frame is created and the code for “main” which had been loaded into the main function object is set as the code object for the execution frame.

Disassembly of the main code object shows this.

7 0 LOAD_CONST 1 (5)

3 STORE_FAST 0 (d)

8 6 LOAD_CONST 2 (6)

9 STORE_FAST 1 (e)

9 12 LOAD_FAST 0 (d)

15 LOAD_FAST 1 (e)

18 BINARY_ADD

19 STORE_FAST 2 (m)

10 22 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (foo)

25 LOAD_FAST 2 (m)

28 CALL_FUNCTION 1 (1 positional, 0 keyword pair)

31 RETURN_VALUE

Now the statements here are almost self-explanatory if they are correlated with the python code itself. I will still explain a few lines to get a hang of how to read this bytecode. LOAD_CONST ‘5’ is done which means 5 is added to the top of the stack in the execution frame.

Each execution frame also maintains a stack which contains the operands which are loaded with the bytecode. As mentioned in the previous blog post, coursera’s course on compilers gives a very good explanation of a stack based machine.

STORE_FAST, then pops the 5 from the stack and assigns it to the local ‘d’. Similarly, ‘e’ is set to 6. The next step is to load both ‘d’ and ‘e’ and then a BINARY_ADD is done to add ‘d’ + ‘e’ and the result is then added to the stack. After that, m stores the value of the addition.

LOAD_GLOBAL ‘foo’ loads the function object associated with ‘foo’ from the module globals and pushes it into the stack. ‘m’ is also pushed into the stack and then another CALL_FUNCTION bytecode instructs the vm to execute foo. A new execution frame is created for the call to foo and pushed into the vm’s execution frame stack.

At this point, the code for foo looks like this.

2 0 LOAD_FAST 0 (a)

3 LOAD_CONST 1 (5)

6 BINARY_MULTIPLY

7 STORE_FAST 1 (b)

3 10 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (print)

13 LOAD_CONST 2 ('Value of b: %s')

16 LOAD_FAST 1 (b)

19 BINARY_MODULO

20 CALL_FUNCTION 1 (1 positional, 0 keyword pair)

23 POP_TOP

4 24 LOAD_FAST 1 (b)

27 RETURN_VALUE

The ‘exec_frame’ for foo executes this code and then return’s the value ‘b’ into it’s parent’s execution frame as the result of the operation.

Another thing to notice is the call to the ‘print’ function. The next section explains this.

Builtins

Builtins are functions which we cannot emulate in the vm itself and the underlying machine is supposed to provide functionality for this. Although this definition is not necessarily accurate in terms of compilers, yet it works in this situation. As in the example above, a call to ‘print’ is done. However, we directly use python’s print method in this case.

The way to implement is simple. When a LOAD_GLOBAL to ‘print’ is encountered, a lookup is done in our globals to find if we have a definition for ‘print’. If this lookup fails, then the vm looks in the builtins module to find. In that case it finds a reference and pushes the function ‘print’ from builtins onto the stack.

Execution of this ‘builtin’ is done in the CALL_FUNCTION, however, no execution frame is used. Instead a normal python function call is done with the args specified and the result is appended on the result stack.

Support for lists, dictionaries are added in the same way as this.

For Loops

As with functions, control flow is also handled in the same way.

def for_loop(n):

for i in range(0, n):

print(i)

def main():

for_loop(5)

main()

The disassembly for the ‘for_loop’ looks like this.

2 0 SETUP_LOOP 33 (to 36)

3 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (range)

6 LOAD_CONST 1 (0)

9 LOAD_FAST 0 (n)

12 CALL_FUNCTION 2 (2 positional, 0 keyword pair)

15 GET_ITER

>> 16 FOR_ITER 16 (to 35)

19 STORE_FAST 1 (i)

3 22 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (print)

25 LOAD_FAST 1 (i)

28 CALL_FUNCTION 1 (1 positional, 0 keyword pair)

31 POP_TOP

32 JUMP_ABSOLUTE 16

>> 35 POP_BLOCK

>> 36 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

39 RETURN_VALUE

The SETUP_LOOP is the main thing to pay attention to. It sets up the for loop in this case. Whenever, the vm encounters the SETUP_LOOP it creates a new Block object and a new execution frame. The Block object stores the code for the loop itself. Also, this execution frame is linked to its parent execution frame so that “locals” lookup could be done.

LOAD_GLOBAL ‘range’ again loads a builtin with the arguments 0 to n. The result of this range call is pushed onto the stack. Now comes the GET_ITER, which turns the top of the stack to an iterable object and pushes it back onto the stack.

The FOR_ITER method, takes the iterable object from top of stack and calls the ‘next’ method on this iter. The ‘next’ is also a python function which increments the iterator.

The rest of the calls are similar until we hit the JUMP_ABSOLUTE instruction. This instruction indicates that our loop has completed execution and we should jump back to the beginning of the loop.

While loop

def while_loop(n):

counter = 0

while counter < n:

print(counter)

counter += 1

def main():

while_loop(5)

main()

For while-loops too, the disassembly is shown below.

2 0 LOAD_CONST 1 (0)

3 STORE_FAST 1 (counter)

3 6 SETUP_LOOP 36 (to 45)

>> 9 LOAD_FAST 1 (counter)

12 LOAD_FAST 0 (n)

15 COMPARE_OP 0 (<)

18 POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE 44

4 21 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (print)

24 LOAD_FAST 1 (counter)

27 CALL_FUNCTION 1 (1 positional, 0 keyword pair)

30 POP_TOP

5 31 LOAD_FAST 1 (counter)

34 LOAD_CONST 2 (1)

37 INPLACE_ADD

38 STORE_FAST 1 (counter)

41 JUMP_ABSOLUTE 9

>> 44 POP_BLOCK

>> 45 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

48 RETURN_VALUE

While loops have the same SETUP_LOOP which does the same thing as the for-loop. However, while loops have conditional expression which cause it to break out from the loop.

The COMPARE_OP and the POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE are the byte codes which enable breaking out of the loop. The logic is exactly the same as For Loops.

Classes:

Classes are slightly more complex than the rest of the concepts to be implemented. That is because classes could have member variables, static methods, constructors, special functions etc. Every method of a class gets an implicit argument of the ‘self’ which is an instance of the object itself.

So lets see how the code looks for this.

class Foo:

def __init__(self):

self.member1 = 1

def print(self):

self.member1 += 5

print("Member1: %s" % self.member1)

def main():

foo = Foo()

foo.print()

main()

The disassembly for the module looks as below.

1 0 LOAD_BUILD_CLASS

1 LOAD_CONST 0 (<code object Foo at 0x7f8d745c1540, file "tests/simple_class.py", line 1>)

4 LOAD_CONST 1 ('Foo')

7 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

10 LOAD_CONST 1 ('Foo')

13 CALL_FUNCTION 2 (2 positional, 0 keyword pair)

16 STORE_NAME 0 (Foo)

9 19 LOAD_CONST 2 (<code object main at 0x7f8d745c1660, file "tests/simple_class.py", line 9>)

22 LOAD_CONST 3 ('main')

25 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

28 STORE_NAME 1 (main)

13 31 LOAD_NAME 1 (main)

34 CALL_FUNCTION 0 (0 positional, 0 keyword pair)

37 POP_TOP

38 LOAD_CONST 4 (None)

41 RETURN_VALUE

The LOAD_BUILD_CLASS is the main bytecode which indicates that a class declaration needs to be built. For this reason python 3 already provides a builtin called build_class. However, during the implementation of this vm, I decided to avoid the use of this builtin and write the code myself to understand how to actually build a class declaration.

So, in our vm this is how it works. When the LOAD_BUILD_CLASS is seen, the STATE of the VM is changed to BUILD_CLASS.

The LOAD_BUILD_CLASS actually is supposed to load a function which builds the class. That is why it provides the code object for “foo” and does a MAKE_FUNCTION after that. So in our MAKE_FUNCION method, if the state is set to BUILD_CLASS then I create a template object which keeps the declaration of this class.

The template object looks like this. It contains the name of the class, the code and a pointer to the original module for globals.

class BuildClass:

def __init__(self, name, code, config, module):

self.__class_name = name

self.__code = code.co_code

self.__ip = 0

self.__stack = []

self.__names = code.co_names

self.__constants = code.co_consts

self.__module = module

self.__klass = Class(self.__class_name)

self.__klass.code = code

self.__vm_state = VMState.EXEC

self.__config = config

class Class(Base):

def __init__(self, name):

Base.__init__(self)

self.__name = name

self.__special_funcs = {}

self.__normal_funcs = {}

The BuildClass is a smaller version of the VM which has support for a few opcodes. So when MAKE_FUNCTION is invoked it creates function objects which are kept in a map in special_funcs and normal_funcs.

One this class is instantiated, it is stored in the global module with the name of the class as the key. Now lets look at the ‘main’ function which creates an instance of this object.

10 0 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (Foo)

3 CALL_FUNCTION 0 (0 positional, 0 keyword pair)

6 STORE_FAST 0 (foo)

11 9 LOAD_FAST 0 (foo)

12 LOAD_ATTR 1 (print)

15 CALL_FUNCTION 0 (0 positional, 0 keyword pair)

18 POP_TOP

19 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

22 RETURN_VALUE

Here, when we do foo = Foo(), that is where an instance of Foo is created and the constructor is called. So a LOAD_GLOBAL of “Foo” is done and CALL_FUNCTION is done. However, CALL_FUNCTION is calling a Class Object here which means we have to recognize this and implicitly call the init method.

So LOAD_GLOBAL here creates a new object from the template of the class. The object is a simple object with no methods.

class ClassImpl:

def __init__(self):

pass

The reason for using this ClassImpl is so that we can then populate the class members and functions. This is populated from the BuildClass klass object which stores all the special functions and normal functions.

Look at the disassembly above. The ‘print’ method from the foo object is loaded. This is loaded from the class object. The ‘print’ function disassembly shows this. LOAD_FAST loads a ‘self’. This is the class object which is pushed onto the stack.

LOAD_ATTR will load the members of the class object and then executes the functions or retrieves the value of the member if its a variable.

6 0 LOAD_FAST 0 (self)

3 DUP_TOP

4 LOAD_ATTR 0 (member1)

7 LOAD_CONST 1 (5)

10 INPLACE_ADD

11 ROT_TWO

12 STORE_ATTR 0 (member1)

7 15 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (print)

18 LOAD_CONST 2 ('Member1: %s')

21 LOAD_FAST 0 (self)

24 LOAD_ATTR 0 (member1)

27 BINARY_MODULO

28 CALL_FUNCTION 1 (1 positional, 0 keyword pair)

31 POP_TOP

32 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

35 RETURN_VALUE