So what are Dominator Trees:

Before understanding Dominator Trees, the more fundamental concept to understand is Dominance. According to Wikipedia, Dominance is defined as a node’s property where a node ‘d’ is said to dominate node ‘n’ if every path from the entry node to the node ‘n’ has to pass through node ‘d’. Every node always dominates itself.

So what is the tree then? Well, when this property is computed for all the nodes in a graph then it is called a Dominator Tree.

def main(a, b, c):

d = 0

if a > b:

if b > c:

c = b

a = b

d = a * c

else:

c = a * b

a = c - b

d = a - c

d = d * 5

else:

d = b

return d

So the next question which comes is what can be considered as a node here in this graph. We just have python code you might say. Look at the IR below. This IR contains instructions and basic blocks.

So what’s a Basic Block? It is essentially a set of instructions which has some kind of terminator instruction at it’s end (for example, branch instructions, or return instructions) etc.

So each instruction can be considered a node or each basic block can be considered a node.

Module: root_module

define main(a, b, c) {

<entry>:

%0 = icmp sle a, b

br %0 1, label %then, label %else

<then>: ; pred: ['entry']

%1 = icmp sle b, c

br %1 1, label %then_1, label %else_1

<then_1>: ; pred: ['then']

%mult = mul(b, b)

br endif_1

<else_1>: ; pred: ['then']

%mult1 = mul(b, b)

%sub = sub(%mult1, b)

%sub1 = sub(%sub, %mult1)

br endif_1

<endif_1>: ; pred: ['else_1', 'then_1']

%mult2 = mul(%sub1, 5)

br endif

<else>: ; pred: ['entry']

br endif

<endif>: ; pred: ['else', 'endif_1']

return b

}

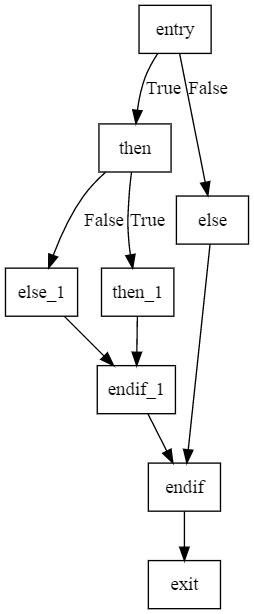

Now look at the CFG above. From this diagram, it is easy to say which node dominates which node or in other words which Basic Block dominates which other basic block.

For example, entry dominates all other basic blocks but it is not dominated by any other basic block.

“else_1” is dominated by the entry and then since to get to else_1 we have to go through else_1.

Interesting block is the “endif_1”. This block is only dominated by “entry” and “then” but not by “else_1” and “then_1”. The reason for this is we can come from “entry” -> “then” -> “else_1” -> “endif_1” or we can take the path “entry” -> “then” -> “then_1” -> “endif_1”.

So in both the paths, only “entry” and “then” are common so we consider only those blocks.

The output below shows the dominance relation between all the blocks. This datastructure is called a Dominance Tree.

<else> --> [<else>, <entry>]

<endif_1> --> [<endif_1>, <entry>, <then>]

<endif> --> [<entry>, <endif>]

<then_1> --> [<then_1>, <entry>, <then>]

<entry> --> [<entry>]

<else_1> --> [<entry>, <else_1>, <then>]

<then> --> [<entry>, <then>]

Implementation:

Wikipedia lists a very simple algorithm for computing dominance. However, there are quite a few good algorithms with discussions on their running times which should be read in order to fully understand the implications of this algorithm.

// dominator of the start node is the start itself

Dom(n0) = {n0}

// for all other nodes, set all nodes as the dominators

for each n in N - {n0}

Dom(n) = N;

// iteratively eliminate nodes that are not dominators

while changes in any Dom(n)

for each n in N - {n0}:

Dom(n) = {n} union with intersection over Dom(p) for all p in pred(n)

The idea is simple. First mark the Dominator block of the entry block as itself since we cannot reach the entry block in any other way.

Next iterate through all the blocks (other than the entry block) and set their dominators to all the blocks (except for the entry block)

Now as long as we have some changes in the dominator tree blocks, for each block other than entry, do the following.

Take the dominators for all the predecessor blocks and intersect them and then union the block itself with the result. So why does this work. Lets take the example of “endif_1”.

So assuming all the other blocks have already computed their dominators, lets trace this through.

Predecessor’s for “endif_1” are “else_1” and “then_1”. Dom(else_1) = { “entry”, “then”, “else_1” } Dom(then_1) = { “entry”, “then”, “then_1” }

so Dom(else_1) intersect Dom(then_1) = { “entry”, “then” }

So Dom(endif_1) = {endif_1} U { “entry”, “then” } So Dom(endif_1) = { “entry”, “then”, “endif_1” }

For my implementation, I have used python set’s to do the intersect method which makes it very simple to implement.

Usage:

Dominator Tree’s are used in a variety of optimizations. We can use it for doing loop optimizations, reordering basic blocks, scheduling instructions, structuring control flow (which was my main interest in implementing this).

Future post I will touch upon how to use this information in the structurizer.